The word Pujabarshiki brings back a slew of memories.

All of Bengal’s leading publishing houses and little magazines would bring out special editions of their patrikas around the time of Durga Puja. Thick with sleek covers, which would either feature the ten-handed Goddess and her four children or a piece of scenery typical of Durga Puja, these volumes would be awaited by young and old alike- for the latter, it was a way of revisiting greener, happier days; for the former, it meant being able to catch up with their favourite characters’ latest escapade or being able to read something (obviously age-appropriate) by authors whose books would otherwise have to be surreptitiously read, frequently looking back over one’s shoulder for signs of approaching authority (considering Satyajit Ray’s Feluda was published in Desh, a strictly adult magazine, our parents, young people at the time, will vouch for this remark).

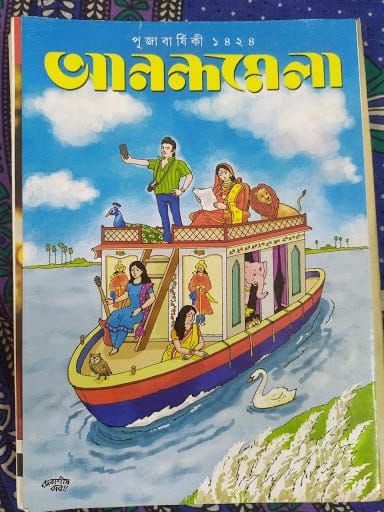

Anandamela Pujabarshiki, Bengali year 1424. Kaash flowers are seen towards the edge of the cover while the Goddess and her children are in a boat. Image Courtesy: Dipanwita Sen

Shirshendu still graces the pages of Anandamela’s annual edition, but there are other childhood favourites who no longer appear between the covers. Kakababu, a retired government servant who’d lost a leg but set off on adventures accompanied by his nephew Shontu, kept children enthralled until 2012, when creator Sunil Gangopadhyay passed away. The last Kakababu novel, Golokdhadhai Kakababu, was posthumously published.

While Kakababu was an explorer and adventurer and not a detective, quite a few detectives have stepped into the literary world from the pages of Anandamela. One of them, Pragyaparomita Mukherjee, assisted by her niece Tupur (who calls her Mitimmashi), is one of Bengal’s only female detectives. Unlike so many of her male counterparts, she has both a roaring professional and a personal life, equally adept at assuming disguises and shadowing potential suspects and helping her son with his homework (her incredible efficiency is a nod to the Bengali adage- Je rnadhey, shey chul o bnadhe). Sadly, awaiting Mitin’s latest exploit, too, is now a thing of the past, creator Suchitra Bhattacharya having passed away in 2015. Interestingly, while most of the stories are for children, a couple of Mitinmashi’s adventures feature adult cases and have not been published in Anandamela.

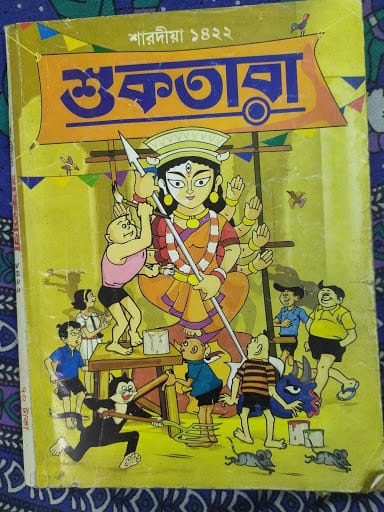

Shuktara Pujabarshiki, Bengali Year 1422. Decorating the idol of Goddess Durga are Bantul the Great, Handa-Bhonda and Bahadur Beral, Familiar faces both in Bengali literary canon and to Shuktara’s subscribers. Image Courtesy: Dipanwita Sen

Shuktara did not rely exclusively on detectives. There were police procedure stories by Subhash De, based often on real incidents, with a young, athletic and intelligent officer called Shushanto Bose and his sidekick, officer Satyen Ghosh. De would mostly write about cases in and around Kolkata, but Bose has also been seen investigating the arms racket in Munger and helping an old colleague in Tripura (regular subscribers will remember some of De’s stories as two or three-part serials in Shuktara’s monthly editions).

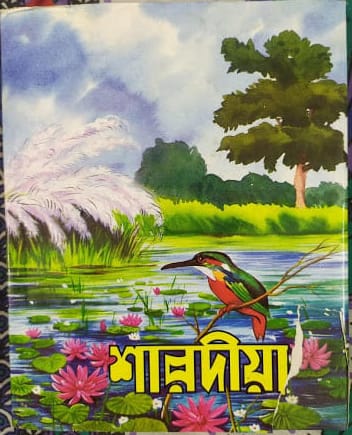

Sharadiya, from Deb Shahityo Kutir, is one of the magazines that existed way before magazines bringing out annual Puja editions were popular. The pond full of lotuses is also a phenomenon attributed to shartkaal, the season of Durga Puja. Image Courtesy: Dipanwita Sen

Pujabarishikis existed way beyond annual extensions of popular magazines, at least where Deb Shahityo Kutir was concerned. When Shuktara was fledging, barely taking its first steps, Puja would be marked by hardbound volumes containing names that exist today not in magazines but in collected works- Ashapurna Debi, Shibram Chakraborty. Sharadindu Bandopadhyay, Tarashankar Banerjee, Premendra Mitra, and more (these have often later been reprinted in Shuktara’s monthly Phirey Dekha section). P. C. Sorcar Sr. wrote articles on magic, often on simple tricks that could be practiced and mastered at home (his son, an equally acclaimed magician, continues the tradition in Shuktara’s monthly editions, while the annuals contain accounts of the Sorcar family’s magic show tours abroad). The books are available, for those interested, in the publisher’s stall in book fairs.

Pujabarshikis remain. So do a new generation of readers- it is we who have changed. The child in us longs for the thrill of the first signs of the approaching Pujas, but we are disappointed by the absence of those who were an integral part of growing up. Something feels missing, hence the oft-repeated rejoinder- ‘Pujabarshikigulo aar aager moto nei.’ Yet, every year, they are as indispensable and as integral a part of celebrations as our new clothes, or the sound of dhak, or kaash flowers dancing in the breeze.